Turf Wars

One of the dilemmas in the art world of the 21st century has been the blurring of lines between artists and critics. In 2004, Maurizio Cattelan ‘interviewed’ Piotr Uklanski as part of an ongoing series for Flash Art. Cattelan has often been regarded as something of a jester in the art world, but in the ensuing conversation between the two artists, Cattelan’s ironic style of interviewing disappeared into the rhetoric of the bully.

MC: So were you… exploiting that French curator on the pages of Artforum in September 2003?

PU: I was doing my best.

MC: Was it also about vanity or about money and compromises? Or just about sex?

PU: It was about the curator’s ass [Untitled (GingerAss), 2003].

Taking the questions as positive reinforcements of his work, Uklanski accepted the Italian artist’s disparaging jabs unflinchingly. With every reply Uklanski seemed to up the ante on Cattelan’s sarcastic rhetoric. Was Maurizio Cattelan aware of being upstaged, out-Cattelan’d by Uklanski? Did Uklanski feel under siege? The performance invoked memories of a television interview with the Sex Pistols and a bunch of punk rockers on British TV in the late 1970s. Fascinated, the audience watched as the punks turned the tables on a supercilious news anchorman – Bill Grundy – resulting in Grundy’s suspension from his job for 2 weeks.

On the pages of Flash Art, the two artists sparred with one another in an epic struggle for territory. Uklanski appeared to possess the wiliness of a 21st century Malcolm McLaren. But as in all “turf wars,” the dirtiest player is usually the one that tries the hardest and wins most often. Game, set and match: Uklanski.

Blurred Lines

If you can’t hear what I’m trying to say

If you can’t read from the same page

Maybe I’m going deaf,

Maybe I’m going blind

Maybe I’m out of my mind

-Robin Thicke

The conversation between Cattelan and Uklanski marks a shifting paradigmatic moment; an example of leaving behind a cultural edifice with set boundaries – between, say, saboteur and promoter – to a fluctuating network where the boundaries of who is “in” and “out” of power is constantly shifting. Uklanski slips in and out of being played with, to being the playa. Like a boxer in the ring, or a rapper swapping lyrics with a fellow rapper, Uklanski weaves in and out of flow, laying claim to the art-lineage that Cattelan (the progenitor) asserts while simultaneously subverting it. In other words, Uklanski performs the crisis of communication at a moment when the culture is transitioning.

Holla at a holla at a holla at a playa,

Remix Baby.

—Jae Millz Ft. Lil Wayne[i]

Whose story is it, anyway? Changing the System

Piotr Uklanski: “…its so hard to decipher the difference between ‘criticism’ and marketing these days.”[ii]

Over the years, a lot of critical writing surrounding Uklanski’s art has been framed solely within the context of a contemporary Fine Art practice that compares and contrasts his art with that of other artists. It’s a familiar method of art writing in which the artist and the writer are validated in their standing within the cultural elite, each one acknowledging the other’s position in the art narrative. This kind of evaluation is so frequently performed that it has turned into a formula. No longer critique, it has now become merely part of the tool kit for promotional marketing.

Uklański is no doubt fully aware of how the art landscape is shaped, if not determined, by the artworld’s full embrace of not just the market but of a marketing ethos. And the artworld and art market are themselves voracious and porous. In the past, art professionals of all stripes took it upon themselves to maintain a safe distance from “lower” forms—even if they might lift a bit as a foil from time to time—to guarantee the authenticity and originality of art, and therefore its market value. But these days the artworld worries less, if at all, about the sacred/profane split. It can well afford to. The artworld takes all into its purview, easily, necessarily, because there seem to be no particulars and few distinctions in our image-saturated and market-driven culture. Except, indeed, the distinction of who holds the wealth. It is notable that this leveling out of culture into a single stream is happening precisely when wealth inequality is exploding. Ironically, participation in the artworld even by the not particularly privileged is also exploding. Tourists flock to New York to shop and to visit MoMA, where, bien sûr, they can shop for all kinds of things at the MoMA store.

When criticism becomes a marketing device it blurs the boundaries between two otherwise distinct processes. Indeed, these two terms have become synonymous in many respects in an era where social networking has raised the specter of self-promotion as de rigueur for anyone doing anything within the field of popular culture. In this sense, resonating with this element of cultural practice, Uklanski’s work embodies criticality while remaining (critically) art.

The artworld has become a highly elaborated construction with its set of institutions—museums, galleries, public spaces, personages, and critical edifice—that produces, markets, and delivers culture as a product. The artword institution constitutes an industry, where categories of art, commerce, criticism, entertainment, connossiourship, real estate, celebrity, and commerce are as permeable as they are promiscuous. The idea of an autonomous art object is a relic. The long moment of the autonomous artist, the genius, often tormented, is also passing. There are no more geniuses, except, of course, in Apple stores. Instead we call actions “genius.” People are playas.

Not every artist working today has adjusted their strategy or persona to this new configuration of the ethos of the culture in general and the artworld in particular, but Uklański has. He is skilled in the enterprise of strategic positioning, of the self not least. Certainly Uklański has not been shy about self-promotion. In fact, he has been exceptionally proactive, the playa indeed, in establishing his position in the industry. He has, in effect, dared the artworld to live up to its brave new self, all the while retaining an aura of coolheaded unflappability. He can make us a bit nervous. He also uses his cool as a cloaking device, and he has landed some punches, or at least made a raid or two into off-limits territory, particularly with the three-page Artforum ad he took out, and personally paid for, in the 2003 September issue. The first two pages of Uklański’s ad, a spread, reproduced his 2002 Untitled (GingerAss), a photograph of curator Alison Gingeras’s behind. It’s a pretty ass and a handsome photograph. The third page is taken up by a text by Gingeras, titled “Totally My Ass,” which begins “Piotr Uklański took a photograph of my ass,” and then rambles on a bit, but then art writing does have a tendency to overstate.

I find exploitation, “self-ploitation,” typecasting, or overexposure very potent formats. —Piotr Uklański[iii]

This is totally my ass.

—Alison Gingeras[iv]

Despite the increasing blurring of boundaries in the artworld, Uklański’s act of literal self-advertisement, complete with commentary by a top curator (and also Uklański’s partner), ruffled some, almost as if Artforum’s glossy ads, as much as the articles, ought not be editorially compromised. Critic Jerry Salz complained that Uklański’s ad was not breaking any rules and was instead playing by them.[v] But that may in fact be the point. Yes, it is worlds away from the photograph of Lynda Benglis naked except for shades and an impressive dildo, which appeared as an ad Artforum in 1974. The fact that Benglis’s kind of critique may no longer be possible, that political challenges are subsumed into and effectively silenced by the culture industry, is evidence of the fundamental change that the artworld has undergone, or as some might say, suffered. It may not be what one would want, but merely wishing it otherwise does not make it so. Neither is Uklański’s Artforum piece a do-over of Jeff Koons’s highly produced self-images in bizarre star settings of the 80s. What distinguishes the Koons suite of ads from the Uklański spread is Uklański’s lack of Koon’s almost frantic need to make sure that irony registers loud and clear, not to mention the fact that each Koons ad includes a line with the names his New York, Cologne, and Chicago galleries. Things are essentially in their place with the Koons ads—the critical distance that allow the images to be and not be what they are, the galleries’ tag line that legitimizes. In the end, although Uklański may be playing by the rules, he also perverts them, which gives us a clue that certain things are indeed over. And, yes, we will remember the ass.

Beyond Appropriation/Embodiment

In our world of scopic overload, the enormity of the issue first raised by Duchamp of how we can operate in an age of constant image flow has now become the only issue. The explosion of the circulation of information and images, of information as image, has restructured our world. As the digital joins and overwhelms the analogue—eats it for lunch—we find ourselves in a new, fused reality, one that is both hyper-reflexive and stupefyingly oblivious, a reality without origin but endlessly sourced. Having made himself a native in this culture, Uklański can’t help but address the altered role of the visual artifact in the construction of meaning. In fact, we could say he is natively drawn to these transmogrifications—of minimalism, of the photograph, of a type of third-generation abstraction, of images of popular culture, of fiber arts and broken-crockery mosaics. Art histories, high and low, have become a stream and a swirl, have entered the larger flow, in which there is not so much a competition of meanings as a confluence. This is Uklański’s source and medium.

While artists like Richard Prince sought, and still seek, to expose a subtext in the appropriative act, Uklański feels no need. What sense would it have in a flow in which meanings comingle in constantly shifting combinations? Uklański has sensed that among the spectrum of viewers—art viewers, television viewers, Youtube viewers, et al—there is a growing, collective awareness that images can hold multiple meanings, an acceptance that they can send competing and often contradictory messages without setting off any dualistic wrangling over meaning. This is not because of some particular quality in the images themselves but because the system of assigning meaning to images is shifting. Whether cause or effect, our sense of time has also changed. There is little sense of a real past that really happened, that isn’t just a collection of random, free-floating images.

Unlike postmodern appropriation, and indeed unlike early Dada or Pop sampling, Uklański’s work embodies the image it lifts. Uklański takes ownership of image flow as art landscape, and in the process he makes our experience of the image overt and points to what we must know ourselves on some level: Our cultural, even high cultural, consciousness has been fundamentally altered by our media- and mind-scape. It exists outside of us, and it exists inside of us. To whatever degree we are consciously aware of the fact, it remains true that culture these days isn’t just a set of objects—like books, paintings, photographs, music, or movies—it is a process, a performance, even, that is staged by and between the culture industry and its audience. The high/low, low/high thorn has been removed from our foot by virtue of the sheer ubiquity of mediated experience, not to mention the sport of documenting it. (When is a selfie not a good idea?) Distinctions that were once hallowed, and even hard fought, now sit easily side by side. In this climate, old strategies of appropriation seem beside the point—not least because any of us digital consumers is also a digital producer, for whom repurposing images is as quick as a laugh and as natural as breathing. Make me a meme. You are now a meme.

If we take memetics seriously then the “me” . . . is itself a memetic construct: a fluid and ever-changing group of memes installed in a complicated meme machine.

—Susan J. Blackmore[vi]

Uklański’s work addresses the altered role of the visual artifact in the construction of meaning.

The work chips away at some of the theoretical underpinnings, tactics, and medium specific characteristics created by newer technologies that have shifted the relations between space, visuality and the contemporary object. Unlike early appropriation art in the late 70s and 80s, Uklański’s work embodies and takes ownership of image flow as art landscape – a landscape primarily dictated by the art world’s full embrace of the market and market forces. Consequently his art goes beyond simple art linear critique and histories and has begun to incorporate the new media literacies on their own terms. If in the past, art was able to maintain a formal distance from other media to authenticate its authenticity as ‘art’, our current cultural condition no longer requires this split. In a culture of spectacle in which we are the spectacle as well as being the producers of the spectacle, everybody has access to a set of media skills that are multi-dimensional and interactive. We are living in a moment of fragmented, fractured narratives that demand new perspectives from both consumers and producers of images.

Embrace the Paradox

As an artist working in the digital era, Piotr Uklański willingly defaults into the role of celebrity in a cultural system that’s all about surface.

Piotr Uklański: “I find exploitation, ‘self-ploitation,’ typecasting, or overexposure very potent formats.”[ii]

Moreover his willingness to play with the rhetoric of visual language as content and context is reminiscent of a scene from The Simpsons where content and context perform each other.

We are all living in a culture of spectacle in which we are the spectacle and the producers of spectacle, both conceptually and literally. Everyone is both creator and audience. We are all engaged in the art of rhetoric, of convincing speech. And in our cultural landscape, where format is more potent than form, the rhetorical naturally supersedes content, becomes the content.

Marge— [Sings] How many roads must a man walk down before you can call him a man?

Homer— Seven.

Lisa— No, Dad, it’s a rhetorical question.

Homer— OK, eight.

Lisa— Dad, do you even know what “rhetorical” means?’

Homer— Do I know what “rhetorical” means?

Rhetoric is the art, art, of persuasive, persuasive, speech. Uklański, the playa, is eminently rhetorical. He is anything but didactic; he is not polemical. He is almost courtly. This is of a piece with the way he and his work respond to the current cultural moment, with its racing megaload of images always in motion, always in the process of transformation. Uklański has his finger on this pulse, for sure, but he also introduces, or perhaps finds, spaces between all these moving parts. It’s not that he stops the flow, it’s more like he finds the curl of the particle wave and rides it. He is in sync with the moving parts, and gives the viewer the opportunity to sync up, too.

Uklański doesn’t worry about producing meaning, that, as he has said, is up to the viewer. But his canniness about opening conceptual spaces for the viewer to make meaning is, more often than not, disarming. He made his mark in New York in 1996 with Untitled (Dance Floor), which he, Gavin Brown, and a friend of Uklański’s, Michal, built themselves in Brown’s Broome Street space. Brown writes beautifully of the toil, tension, and sheer, wild ambition of it all, describing the three of them as a mathematical set defined by the term “belief in disco floor.”[vii]

You can ring my bell, ring my bell

(Ring my bell, ding-dong-ding, ah)

You can ring my bell, ring my bell

(Ring my bell, ring-a-ling-a-ling)

—Anita Ward[viii]

People have described Dance Floor as an irreverent quotation of minimalism, particularly of the stern, Carl Andre sort, but it actually looks a whole lot more like the dance floor in Saturday Night Fever. If there is a minimalist quotation, it is easy and unforced. Whatever—disco floors, Dance Floor, and Carl Andre inhabit the same cultural space, because all have moved, or been moved, into the flow. (Can’t you just see a selfie of someone in a John Travolta pose on one of Andre’s metal plate floors? If it weren’t for the guards . . . but then, it could be Photoshopped.) As moving parts in the same image landscape, these three elements are not as discrete as they may have once been; certainly it is not Uklański’s aim to fix them in separate realms. He does not insist on enough of a distance to generate strategies of appropriation and its theoretical critiques. Or perhaps it would be closer to the truth to say he lets all three settle where they will, and lets the artifacts of their small differences resonate, if they will, without comment. Then he gets out of the way. The work is, after all, made for dancing. In the end, there is a weird tenderness in Dance Floor. We are persuaded, yes.

We are persuaded because we inhabit this hybridity; it is so natural to our moment that we hardly notice it. Time collapses, too, along with other distinctions. We are no longer in the territory of the Lacanian floating signifier, which, potentially at least, ends in meaning, is resolved in a future “will have been.” Arguing that information technology has brought about a profound change in the relationship of signified and signifier, N. Katherine Hayles posits instead a flickering signifier. Meaning is not emptied out; it remains restless and untethered. Time cannot be divided into a time before understanding and a time after comprehension. We live in a constant present, though not the present of contemplatives. Our state of present-ness is always buzzing. Meaning never settles down. There is little rest. We sleep with our iPhones.

Digital/Viral/Intercultural Slippages

Uklanski’s work navigates the current media landscape (with all its minefields for the uninitiated artist or critic) skillfully and with an understanding of the aesthetics of pop culture. His works play across multiple platforms. He is adroit at mastering the tools of new media literacies, so that the work retains flexibility in every potential area it participates in. In fact, much of his art making has the ability to act viral, slipping into different groups and different spaces with an awareness of what the norms of the different groups and spaces are.

Much like a video game, Uklanski’s art takes the concept of play seriously, embracing the capacity to experiment with its surroundings as a form of problem solving.

Specifically, Uklanski’s photographic work from the ‘90s to the present originated within the bounds of the artist’s intentions and as such, visually contained the sub-textual layers in his subterfuge of the mechanisms of culture. But in our current state of image fluctuation and flexibility of meaning in the digital age, the mass populace of pop culture has absorbed much of what was once considered to be the terrain of the artist. That is, to manipulate meaning for the sake of playing with image. Now, any digital consumer is also a digital culture-player; anyone can read, use and manipulate the image with the methods and vocabulary that the appropriation and conceptual artists of the ‘80s and ‘90s established.

The Pop Culture Aesthetic

Defining what the digital landscape has created culturally, we are aware that popular culture these days isn’t just a set of media objects (like novels, music or movies,) but a process that takes place between an audience and the culture industry. Moreover, the culture industry has become a set of organizations, institutions and businesses that produce culture as industry. And since art, artists and art objects have become a part of the culture industry, they now participate in this process. The process doesn’t have to involve mass culture. So even if art doesn’t reach the masses in the same way that other forms of popular culture do, it’s still a participant in the process.

This is the result of the marriage of commerce and the arts. Of course when we look back to the artist/patron relationship during the Renaissance, it has always been thus. But now the connection is with the electric, the digital. Like the stock market whose physical representation, Wall Street, is merely the ghosting of the concept, Uklanski performs the inevitability of the contemporary artist in the digital age. There’s a subtle difference between say, his work with film stills depicting Nazis and Richard Prince’s work with the Marlboro Man advertisements. While Prince sought subtext in the appropriative act, Uklanski doesn’t even need to do that; it’s already present. All that’s needed is the viewer’s reaction to complete the enterprise as artist.

Even in his early works, Uklanski began to understand that within the spectrum of viewers – television viewers, art viewers, Youtube viewers et al – there was a growing, collective awareness and acceptance that images can hold multiple meanings; that they can hold competing and often contradictory meanings. And that this is not because these images were extraordinary in themselves, but because the system of looking was shifting.

Jamming the system/In search of a shared language

In the 21st c. digital technology has changed the balance between the producer and consumer of images. Users of the Internet and participants in platforms like Youtube automatically and paradoxically both collapse the distinction between high culture and popular culture as much as they sustain those distinctions.

While reflections and critiques about issues of appropriation and imitation abound in art world conversations as they seek to find a common language with which to talk about contemporary art, appropriation in the digital age has simply become a genre – like landscapes and portraiture. What’s less common is a critical framing of artwork within the cultural context of hybridity.

Who’s On Third?

At some point every kid latches onto the fantasy of having an unknown twin somewhere in the world, a lookalike who is not a blood relation, who would be a pal like no one else, an other who is the same. Although a phantom fascination with the possibility of twin other self may linger beyond childhood, as adults, more often than not, we come to view the other as alien, even perverse. Even our common usage of “the other” implies an exclusion from whatever group we identify with. So what about the otherness of porn-stars? There are doubtlessly multiples more consumers of pornography than porn actors and models. As intimate as our imaginative connection might be with them, they are the others; we are not. And porn-driven or not, the power play of who is other and who is not, who is the object and who is not, by its nature carries a sexual charge. We are of course in the realm of the gaze and the erotic control that the eye exerts over the object of its attention.

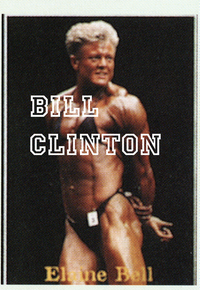

Enter Uklański’s Pornalikes (2002– ), an ongoing series of images culled from porn magazines and websites that the artist has been collecting for several years. The photographs are installed on a single wall, in a grid that stretches top to bottom and side to side. What makes the pictures particular is that the actors have been tagged with names of celebrities they resemble. And they do. The celebrity tag comes along with the image; it is not an add-on by the artist. On one level, the Pornalikes are a deliciously corny riff on the separated-at-birth joke that cast the found-object form in a new, multiplying light. They are themselves, as images lifted from magazines and the Web, found objects, ready-mades, “others” vis-à-vis the art object traditionally defined. As pornography, the actors are also images of objects of desire, “others” by definition, who as it turns out, look like others they are not. And then, piling on the permutations of otherness, the gender of the celebrity and the star don’t always match. Bill Clinton is a super-buff bodybuilder type, but a woman. Celebrities themselves are another order of the other, people we know all about who we don’t actually know. Yet, as with any object of the gaze, we possess them whether they would will it or not. And we, too, as viewers are other, subject to the gaze of other viewers as we take our pleasure in the images. By the end of it, the intertwining of othernesses yields to, even generates, a chatter of flickering signification.

Enter Uklański’s Pornalikes (2002– ), an ongoing series of images culled from porn magazines and websites that the artist has been collecting for several years. The photographs are installed on a single wall, in a grid that stretches top to bottom and side to side. What makes the pictures particular is that the actors have been tagged with names of celebrities they resemble. And they do. The celebrity tag comes along with the image; it is not an add-on by the artist. On one level, the Pornalikes are a deliciously corny riff on the separated-at-birth joke that cast the found-object form in a new, multiplying light. They are themselves, as images lifted from magazines and the Web, found objects, ready-mades, “others” vis-à-vis the art object traditionally defined. As pornography, the actors are also images of objects of desire, “others” by definition, who as it turns out, look like others they are not. And then, piling on the permutations of otherness, the gender of the celebrity and the star don’t always match. Bill Clinton is a super-buff bodybuilder type, but a woman. Celebrities themselves are another order of the other, people we know all about who we don’t actually know. Yet, as with any object of the gaze, we possess them whether they would will it or not. And we, too, as viewers are other, subject to the gaze of other viewers as we take our pleasure in the images. By the end of it, the intertwining of othernesses yields to, even generates, a chatter of flickering signification.

And if thine eye offend thee, pluck it out:

it is better for thee to enter into the kingdom of God with one eye,

than having two eyes to be cast into hell fire.

—Mark 9:47

Into this, across the room from the grid of images and at the viewer’s back, Uklański suspends a huge eyeball made out dyed and stuffed fabric. It looks as if it were torn from its socket and hung out in the air. It might blow in the wind except for the weight of it. Instead it is still, unblinking, and looking at you look. It is hilarious.

Jeopardy Answer: What is Hybrid Culture?

The fragmented hybrid is the signature of our age. This is the cultural turn of this century. We’ve moved away from the direct binary into the playing field of multiple negotiated and renegotiated languages.

Critical awareness is what counts.

It’s what makes the difference between the activity of art and certain kinds of everyday cultural practices. This concept is illustrated in the book, You Talkin’ to Me? by Sam Leith in a discussion of 21st century criticality:

“Like a fish in its water, we can and do swim (in it) unthinkingly. But there is so much that you miss out on if you don’t stop to think about it. Understanding rhetoric makes you better able to appreciate its wonders and pleasures; it equips you better to use it yourself . . . But it’s even more than that. To think about rhetoric is to think about something central to the foundation of our politics, to the DNA of our culture and to the basic workings of the human mind.”

The critical mind usually avoids binaries. Uklanski understands this well.

Let Me Persuade You of Joy

We say “empty rhetoric” but don’t really need the modifier. In contemporary usage, the word “rhetorical” almost always implies a lack of authenticity, a ploy to avoid dealing with a problem, a tactic that obfuscates the real issue. Aristotle himself admitted that the art of rhetoric could be put to less than desirable ends. And that, strictly speaking, the truth or virtue of an argument lie outside of rhetoric’s domain. In the art of rhetoric, it is enough to simply convince.

Yet for all our contempt of the word, the ubiquity of advertising has made us fluent in rhetorical speech, at least in the realm of the marketplace. We understand it; we speak it. It is the lingua franca of marketing campaigns—marketing of politics, products, and self. And we are not so naïve that we do not know, au fond, that what this marketing speak is saying is in essence untrue. When we are willing and complicit in the lie, is it still a lie?

Uklański’s Joy of Photography photographs are irresistible. So is his book that compiles a selection of fifty of them. They are almost too good to be true. They are that, too good to be true, in fact. They are eminently rhetorical and persuade, even as we know they are not telling the truth and worry a bit that they have little virtue. The subjects are mostly landscapes, cityscapes, and skies, the commonest of romantic motifs, but never tiresome. We want more candy. The Joy of Photography is an ongoing series that Uklański began in 1996. To make it, Uklański studiously followed the instructions in Eastman Kodak’s seminal how-to guide for amateur photographers, its The Joy of Photography, which first appeared in 1979 and was reissued in several succeeding editions. Uklański proves himself an outstanding student of Kodak’s brand of “personal vision,” which, of course, was studied—how to get specific effects with which lens, what shutter speed, what exposure, what framing—and executed by thousands. Uklański out-executes most, at times following Kodak’s examples almost exactly, at times applying a mastered technique to a different subject in a new way.

Uklański’s Joy of Photography photographs are irresistible. So is his book that compiles a selection of fifty of them. They are almost too good to be true. They are that, too good to be true, in fact. They are eminently rhetorical and persuade, even as we know they are not telling the truth and worry a bit that they have little virtue. The subjects are mostly landscapes, cityscapes, and skies, the commonest of romantic motifs, but never tiresome. We want more candy. The Joy of Photography is an ongoing series that Uklański began in 1996. To make it, Uklański studiously followed the instructions in Eastman Kodak’s seminal how-to guide for amateur photographers, its The Joy of Photography, which first appeared in 1979 and was reissued in several succeeding editions. Uklański proves himself an outstanding student of Kodak’s brand of “personal vision,” which, of course, was studied—how to get specific effects with which lens, what shutter speed, what exposure, what framing—and executed by thousands. Uklański out-executes most, at times following Kodak’s examples almost exactly, at times applying a mastered technique to a different subject in a new way.

The Joy of Photography will help you become visually articulate,

the first step toward achieving a personal vision in photography.

—The Joy of Photography[ix]

The pictures glow. They do not seem ironic in the least. They pose no resistance to the romanticism and skewed idealism of the original models. If anything, Uklański ups the ante with the best personal vision ever.

The Digital and the Hybrid

Without question, culture today is completely shaped by the digital. Technology has become the water in which we swim. We use it, but do we consider its implications? Are we in the best ocean? A fish can’t become conscious of water the way that we as humans can step back to critically evaluate our relationship to technology. And in today’s culture, that evaluation requires a close analysis of hybridity.

Hybridity, in our cultural moment, is multi-voiced and singular at once. It strays from Jacques Lacan’s idea of the floating signifier (the meaning that can only be defined by what it is not) to N. Katherine Hayles’ flickering signifier. The meaning changes always and simultaneously. Artists have played with this idea for some time, but through digital technology, mass culture has caught up. Now we are all objects with multiple meanings and purposes. With this in mind, considering Piotr Uklański as an artist means that we must approach him as a cultural object in his own right. As Gavin Brown said, Uklański “out Koons Jeff Koons.” In many ways, Uklanski is performing Koons- who performs the artist commodified.

Celebrity/Identity

As an artist working in the digital era, Piotr Uklański willingly defaults into the role of celebrity in our current cultural system that is all about surface. Referencing the quote again from Flash Art in 2004:

Piotr Uklański: “I find exploitation, ‘self-ploitation,’ typecasting, or overexposure very potent formats.”[3]

The success of this kind of art depends upon an awareness of the pop aesthetic. Uklański is both art playa and bona-fide artist, deeply ensconced in the art world. But it’s the uncontrollable life of his image and images of his artworks online that takes on the more complex multi-vocal life.

How does Uklański’s work and self-image get read in this current age of mass culture where playing with visual language is now second nature to all Internet users?

Uklański’s Joy of Photography is a carefully, thought out framing of pop culture’s perception of the ideal image. But this kind of play is common faire throughout the digital space we currently occupy. From Psy’s Gangnam Style, a self-acknowledged skewering of the posh consumerist culture in Korea, to any of the myriad viral memes currently getting their one billionth hit, the images concocted are popular because of their self-reflexive acknowledgement that they are part of the system of meaning while simultaneously being the saboteurs of that same meaning.

In many ways the popular viral meme that surfaced in 2006 on Youtube, generally referred to as “Downfall” (or “Hitler reacts”), resonates profoundly with Uklański’s Untitled (The Nazis) and its relationship to the mythos of the Nazi/Hitler image. Uklański’s Untitled (The Nazis) is a collection of film stills depicting actors in military uniforms from American and European movies. The initial reaction towards this piece was splintered between those who recognized the actors as performers and others who only recognized the uniforms as fascistic or outright Nazi garb. It is the difference between appreciating the witty, ironic gesture and condemning the glorification of Nazism. With this ambiguity of origins (film or historic document?), Uklański leaves the reading of the images open to the viewer’s own conclusions and hence visceral reactions or entertainment.

MC: … What about the meaning of the work then? Do you care about it? I mean, there is the Dance Floor, which people say is a social sculpture, and then The Nazis, which is about violence, and the collages about banal beauty maybe.

MC: … What about the meaning of the work then? Do you care about it? I mean, there is the Dance Floor, which people say is a social sculpture, and then The Nazis, which is about violence, and the collages about banal beauty maybe.

PU: The Nazis about violence? You know, I don’t invest meanings into the work — that’s the viewer’s job.”

There is also the subtext of these images as incorporating desire – movie stars, iconic roles etc. – and the impeccable uniforms as symbols of both authority and violence and cosplay. Uklański’s appropriation and re-staging of these film stills, within the gallery space, intersected meaning and long-held assumptions within the visual relics of World War II. This parallels the Downfall (Der Untergang) meme as it constantly re-inscribes the subtitles of a pivotal scene in a film about Hitler’s final ten days in Nazi Germany. In the original film, there is a critical scene when Adolf Hitler finds out from his generals that he is set to lose the war as a result of losing a series of crucial battles. The scene plays out in what amounts to a tirade from Hitler as he unleashes accusations and condemnation upon his generals. Within the film’s narrative, this scene is a turning point in the narrative and a humanizing look at Adolf Hitler.

Soon after the film’s release, Internet users who inserted their own subtitles, replacing the original scripted dialogue, appropriated the scene. Through the Downfall meme, Hitler has now become the ranting megaphone over a variety of cultural banalities, from complaints regarding Disney buying the rights to the Star Wars franchise to an angry reaction to the iPad, to a rant about the parody meme itself.

In like manner, Uklański’s project, Untitled (The Nazis) negotiates the visual connections between the illusion and the emotional history that has accumulated over the Nazi image. The 122 film stills that look identical to one another – the stills look like military portraits of soldiers- further flatten the symbol and ideas that are held in the image, allowing them to become empty objects of desire.

The viral meme however goes beyond Uklański’s one note as the exponential number of memes that begin to accumulate empty the visual symbol and power of Hitler completely. This is what communication theorist Henry Jenkins describes as the effect of “convergence culture,” where the audience are simultaneously the viewer and contributor/producer of the same culture. [4] Uklański’s work carefully constructs the criticality within the work. With the Downfall meme, the critical expression belongs to no one and is every participant’s design. This is an indication that appropriative constructive practices has in many ways, itself gone viral – it is beyond a formal art expression. It is the primary means of cultural expression.

In many ways, Uklański’s methods have become the new Joy of Photography where viewers, aware of their own cultural idealism as being a flawed perspective, remake and sabotage their own ideologies for the sake of being entertained. The difference between Piotr Uklański and the current digital user is that Uklański, as an artist, is highly self-aware of his artistic strategies while the digital participant reacts instinctively in their appropriation of visual language. Culturally, a distinction is made between Uklański’s methods as an aesthetic practice while the appropriation acts of the masses is viewed as artifact.

Really?

But is there such a big difference between the two forms? Once images are set loose in the digital ether, whether it’s a refined photograph titled Ginger Ass or a film still of Jennifer Lawrence’s ass from Silver Linings Playbook (or better yet, the hacked nude selfies from JLaw’s iCloud account,) these objects begin to have an equal footing as simulacrum. They are not quite what they purport to be and in the end, slip away in their intentional meaning to point us towards someplace else. When considered in light of this kind of contextual slippage, the artist known as Piotr Uklański, is no longer who he says he is but rather, at various times, is many things and nothing, all at once.

Community Forum: It’s not Socialism: It takes a Village …

The rhetoric of individualism and the auteur is also a topic called into question in the 21st century. Uklański understands that you need a team to create the object or product, to make it go viral. Lady Gaga worked with Inez Van Lemsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin to produce Applause, but she also knows she needs her “little monsters”, her fans to co-produce the end product. Kanye West had multiple sessions with multiple collaborators including Bon Ivers, Justin Vernon, producer Hudson Mohawke, and many more who helped create Kanye’s polarizing thunderbolt of an album, Yeesus. The cultural shift that has taken place in this century requires this concept of “community” to construct and deliver the commodity. Indeed, the criticality embedded in the digital is never defined by a single voice. It always gathers together a cacophony of voices. In many ways this is precisely what Uklański’s work performs, so it makes sense that it’s precisely how we should interact with it too, as critics – or, if you will – as participants.

Classically, the art of rhetoric and the art of memory go hand in hand, although memory as a classical art was an elaborate system of placing images throughout an imagined edifice, a memory palace seen in the mind’s eye. A walk through the memory palace, furnished with its images that evoked different points of a discourse, provided the speaker with an elaborate mnemonic device. It has been a long time since a speaker has needed such a device, even before our age of Powerpoints and teleprompters. Still, Uklański’s rhetorical gestures, for all their immersion in the flow of presentness, do contain the tug of memory. More than quote a lost pre-digital era, Uklański reenacts it, with care and, one must believe, pleasure in The Joy of Photography. This does not feel like an act of postmodern appropriation, because there is no sense of a strident us/them, now/then split. This quality is present in other works too—in Dance Floor, obviously, in the outdated type and graphics of the Pornalikes, even in Ginger(Ass), which in an age of naked-bum selfies, whether hacked or freely launched, seems positively classical. It is the faculty of memory Uklański engages as much as the remembered thing. It is the frisson of memory within the overloaded flow of our manic presentness, proffered without judgment, either aesthetic or political. Whether or not this represents the truth of any matter, whether or not it is even possible to lay claim to truth, need not matter to the rhetorician.

Slurpee, (2016), acrylic on wood diptych.

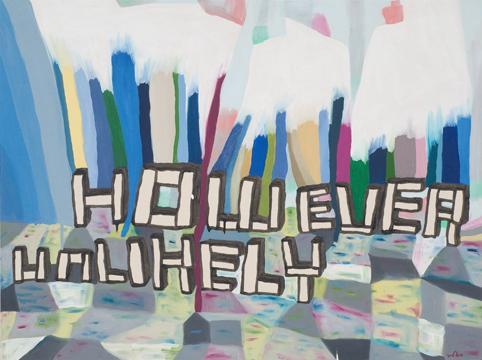

Slurpee, (2016), acrylic on wood diptych. However Unlikely, (2009), oil on canvas.

However Unlikely, (2009), oil on canvas. Polka 3, (2014), fabric collage and india ink on paper.

Polka 3, (2014), fabric collage and india ink on paper.